George Hancock (b.1896) lived and worked at Sheephill Farm, Ringinglow. Here is Alan’s adaptation of his reminiscences, taken from Dr Ian Russel’s 1974 Ph D thesis: Singing in West Sheffield 1970-2. – White Rose eTheses …

George Hancock was born on 7 November 1896 at Carsick Hill Farm, Fulwood. He was the second eldest of eight children. When he was six years old his father acquired Sheephill Farm near Ringinglow, and there George has lived and worked for most of his life.

The Hancocks have been connected with Ringinglow since it came into being in the eighteenth century on the crossroads of the old Hathersage turnpike road. In fact, a large part of the village was built by members of the family.

Grandfather Henry Hancock had been the local ‘squire’, owning large portions of the village including the Norfolk Arms, Brown Edge Quarry, and Sheephill Farm. George recalls with pride,

‘all t’ men int’ village used to work for me grandfather, we didn’t ought to have to work for us living at all’.

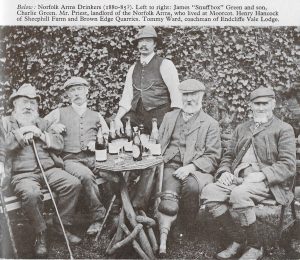

Henry Hancock and friends at the Norfolk Arms (Muriel Hall’s More of the Mayfield Valley, 1974)

Henry Hancock and friends at the Norfolk Arms (Muriel Hall’s More of the Mayfield Valley, 1974)

But Henry’s affluence was to be short-lived.

“E blewed it all in after me grandmother died.

‘Peggy Leg’, as he was nicknamed after he had lost his leg in a mowing machine accident, drank himself slowly to death and the only family asset that survived was the farm. George’s father, Robert, took this over and although he was not as colourful a figure as ‘Peggy Leg’, he was much more reliable and hard-working. Like his father, he combined farming with stonemasonry. He built several cottages in the village and worked on the construction of the Dore and Totley Railway Tunnel (1894) in which he was responsible for the stone arches that provide the support. George’s wife, Edith, notes that Robert was a strict master in his own house,

‘they [grandchildren] were all frightened to death of him. He used to look at ’em.’

George attended elementary school up to the age of thirteen. For his first two years he went to Fulwood Church School, thence to Whitely Wood and for the last year to Dore School. Money was always short and from an early age George was expected to pull his weight on the farm.

‘It were ‘ard. We had to work ‘ard. We used to grow fields of turnips then. We should have to hoe a couple or rows of turnips afore we went to school in the morning. When we come ‘ome at night we had to go into t’ turnip field hoein’. He [father] were tough.· He were hard as nails.’

As an older child, George was also obliged to help with the housework and to look after his younger brothers and sisters.

We used to have a rocker, t’owd cradle there. I’ve sat hours here, foot on cradle, rockin’ ’em to sleep. I’ve sat hours there, while I’ve been sick to death. They wouldn’t go to sleep. There’s many a time if they were wrong road out, I used to go to bottom of stairs and shout upstairs to them — they’d be cryin’ upstairs I used to go and shout, ‘me father’s comin’ up yard – there wouldn’t be another sound.

However hard the life must have been it had its compensations, and George remembers there were happy times. In the evenings they used to gather round the fire and their mother and father would sing to them. Neither parent could read music nor play an instrument and all the songs were performed from memory. Often friends from the village would call for milk and stay on to talk or play a game of darts, dominoes, or ‘Ludo’. It was at these family gatherings that he learnt his first songs. George’s mother was a Marsden, born at Carsick in Fulwood, and he was especially fond of her. On one occasion he walked to Redgates’ shop on Sheffield Moor (a twelve-mile round trip) and spent his total savings, five shillings, on a cart to serve as a pram for his mother to push the children in. This attachment to his mother is echoed by two of his songs. The first declares,

‘Dear old mother always kind and true, Dear old mother, I always think of you. When this world departed and the time when you are old, ‘Tis then you’ll find your mother is the truest friend of all’.

An extreme form of the same sentiment is demonstrated by the second song, which is a great favourite with female company. George’s mother-in-law used to sing it.

‘I do love my mother as my life. Once I thought I’d like to take a wife, When I mentioned it to mother dear, In ‘er eye I saw they were a tear. Do not leave me now I’m old, she cried. You’ve been my only pride since father died. Do not let another come between, Be to me the son you’ve always been. For you know I love you more than words can say, t’would break my oId heart if you went away, For you and your sweetheart may fondly love each other, You can get a sweetheart any day but not another mother.’

As a child George had witnessed the last few years of his grand-father’s decline, and such examples of habitual drunkenness, which were then commonplace, have left a deep impression on him. At the time, however, he and his brothers treated such characters as his grandfather as objects of amusement and fair game. Thus, they would lie in wait for the drunks leaving the pub.

‘We used to go tormentin’ them as were canned up … and they’d run us and it suited us down to the ground. We ‘ave ‘ad some does. Course they couldn’t catch us.’

It is understandable that George himself has never been a heavy drinker, and yet his attitude towards drunkenness is ambivalent. Although aware of the injustice perpetrated by drunkards, in that the week’s wages would be selfishly squandered on beer to the neglect of the family’s welfare, he does not condemn nor condone such men for their irresponsibility. Nor is he unsympathetic to their predicament but speaks affectionately of men such as Tommy Peat who regularly went on’t spree.

‘Old Tommy Peat he lived in first ‘ouse up here. He used to work for me father. He were hard’ workin’ chap, good stonemason … He were the quietest chap out, but every night, after ‘e’d ‘ad his tea, when he come ‘ome at night, he’d take a jug and go to t’ Norfolk and fetch a pint out, and drink it in t’ house. After he’d had that in house, he’d go in for last two or three hours ….He lived on it nearly. When he’d saved a bit of money up he’d have a week off. He’d be drinkin’ all t’time.[laughs] He used to sleep. Rough…. We knew when he’d finished spending his money, when he were getting to the end of his tether, he used to come ‘ere early in the morning … Old Liza Peat, his wife, she used to be hot pot wi’ ‘im. Used to tan ‘im like. He’d come ‘ere. I’ve seen him come to this door early in the morning an’ me mother’s gone to t’door. He knew we’d a barrel. He’d called to see if we could let him have a drink of beer, you know, first thing. He’d have to start workin’ again and savin’. He were grand chap, he were quiet chap, he were harmless but he loved his drink. I can remember hearing my mother telling him one morning. She says ‘I’m just gonna mash some tea. Won’t you have a cuppa tea?’, ‘Nay he says ‘no, that don’t quench me’. He wanted a pint of beer. He were a terror for work. George also has mixed feelings towards hunting. ‘It’s cruelty. I don’t like it meself, not now. But we used to enjoy it them days. Whenever the Hallamshire Harriers or the Ecclesfield Beagles visited the neighbourhood everyone took a holiday to follow the hunt, and afterwards there was always a singsong at the Norfolk Arms.

Thus far, George’s childhood had been relatively happy though hard. This security was to come to an abrupt end when he was twenty with the conscription of him and his brother Albert. George’s single most vivid reminiscence relates to time spent at the front during the First World War with the army. Initially his eldest brother Maurice had volunteered in 1914, but because he was not fit he had been placed on a farm near Loughborough; and that left just George, Albert and their father to work the farm. When recruitment became difficult in early 1917, conscription was stepped up and farmers’ sons were given no special consideration. First Albert received his ‘call-up’ papers, and then three weeks later George received his. Their father was at his wits’ end, and, unsuccessfully, appealed against the decision.

‘They went an’ took us because they told him as he was strong enough to do t’work. Strong chap. I shall never forget when he went to Derby. He went to appeal for me … an’ it were beginning of hay time. All hay in t’fields and there were some good crops and was only ‘orses to get it. They took me. When he come back had tears in ‘is eyes. When they came to look round yard he were broken hearted… There were four of ’em to bring up besides, you know, younger than eight [years] in family.’

Despite their father’s plight, at the time George and his brother were quite pleased to be called up as all their friends had gone, while work on the farm was harder than ever. They received only four months training and George never saw his brother again.

I went over same ground as ‘im … I got his address from home. Blow me, when I were in ‘Flanders’, we were out for a rest there, I went to look for ‘im. I were goin’ to take ‘im by surprise. I found their batallion were out on rest same as we were. I went to their HQ in an old mill. They were billeted. You got anywhere ‘cos everywhere was smashed up. You were in cellars. You’ll get anywhere for cover. I got wi’ ‘is pals an’ ‘e weren’t there. I sent word ‘ome about ‘im before War Office …They were in old factory there, I can remember looking through the factory an’ it were at night when it were dark. You daren’t show any lights, you know, and they’d just got candles. They were a lot of ’em pickin’, they’d got their trousers an’ that, pickin’ lice off.’

It is no wonder that George found little to sing about from these war years; in fact, there is not one item in his repertoire that originates from his time in the army.

‘There were dead all over t’place like, terrible really. Sights you never forget, you know.’

After being discharged from the army, George went back to help his father on the farm. They kept a small dairy herd of about twenty to thirty short-horns, a few pigs and some poultry. The day’s work began about 5.30 a.m., George says they were the first farm to be up in the neighbourhood, and finished about 6.00 p.m. It was punctuated by two milking sessions and after each, a milk round. These sessions were, of course, one of the two regular occasions for singing. .

‘We were always singing when we were milking and doing in t’cow’ouse. The other was in the pubs. All t’ pubs you used to go to round about there’d generally be a good sing. Before I were married I learnt a lot of them [songs]. Nearly all t’ local places there’d be somebody who’d generally say ‘who’s thee mate? Get up and give a song’ It’s gone on for ages like. We used to hear some good songs. It were worth going to a pub.’

He also used to visit his Uncle Joe Hancock and Aunt Sebra at their cottage in Whitely Wood. They were both singers and George says that he learnt ‘The Gallant Hussar’ from them. Christmas was perhaps the most musical time of the year. One evening when he was returning from the Three Merry Lads, George came across a group of carol-singers and joined up with them. It was to be a long session for they were out all night and sang to most of the neighbouring farms and cottages.

‘All ‘ouses we went to, they opened door. It didn’t matter what time we got there. They’d get up and open door for us to go in with, have a real good sing. They’d fetch mince pies out. They were grand nights. We really enjoyed it.’

It was on that very night in 1925 that he met his future wife, Edith Allen, who was a member of the carol party. Later at the wedding, George sang appropriately, At Carsick I was bred and born. At Sheephill is my dwelling. I fell in love with a pretty fair maid, And ‘er name were Edith Allen. For their first few years they took a cottage at Jeffrey Green, Fulwood, or ‘Ratten Row’ as it is known locally. Other occupiers of the seven cottages included two noted singers, Riley Marsden and ‘Aunt’ Jane Marsden (not related).

‘It were best row there were in i t’ country’ We ‘d have a choir of us own… We were always singing …. We used to have a piano on at night … They don’t neighbour like we used to do then. We were all good pals, you know, always makin’ fun. It was Edith who played for the singing. She was also the organist at Mayfield Chapel. Although her mother was a singer, she herself is not but she does like to join in with George. Their next move was to a small farm in the Peak at Litton near Tideswell. They were only there for two years before returning to Sheephill, he took over the farm and has lived there ever since.

The farmhouse itself is divided into two parts and his son Noel occupies the other half, another son Peter lives in the nearby tied cottage, while the third son Roy lives in the next village, Dore. The farm is set into the side of the moors just inside the Peak District National Park, and commands a panoramic view of the city, as well as of Bolsover and Chesterfield on a clear day. The interior has changed considerably since George’s childhood. The parlour for instance, which serves as kitchen, dining room and lounge is now comfortably furnished with a fitted carpet, modern tiled fireplace, comfortable three-piece suite, two large dark dressers, a cooker, dining table and chairs, and the whole bestrewn with brass trinkets and photographs. Only a few features have survived that recall, for George, the room as he first knew it, namely the grandfather clock, the long shallow enamel sink, and the hooks in the ceiling which had formerly supported curing bacon, but now carry an indoor washing line. Gone is the pegged rug that stood in front of the fire, and the hopsacks which had covered up parts of the tiled floor, the Yorkshire range, the large bare wooden table, the form and the wooden rocker. Outside, the changes on the farm have been equally substantial. Since the introduction of various regulations governing milk production, as well as the modern methods of bulk collection, the dairy herd has been discontinued, although the milk round is kept on. Today the farm, about forty-nine acres, grows some barley, potatoes and hay; and the stock includes a few young ‘fat-stock’ cattle, thirty pigs, some chickens, and five riding horses (pastured there). The work has changed considerably for the farm used to support three or four men full-time, but now there is not the work for one. Noel, who has managed the farm since George’s retirement, works four days a week as a full-time joiner and stonemason, whereas Peter, who helps out at feeding times, spends most of his day working on a much-enlarged milk round. Nevertheless, in 1974 he demonstrated the high degree of skill and craftsmanship that still exists in the family by winning the National horse-drawn ploughing championship at Ross-on-Wye. George, himself, since leaving hospital has been leading an active life, visiting Bakewell Market on Mondays, taking walks around the farm, building for himself seats and shelters at vantage points, buying himself a car, and attending social evenings at the Mayfield Community Centre. There the typical evening activities, which include whist drives, dances and illustrated talks, have appealed to George; and since his return to Sheephill his visits to pubs have become infrequent. After all, the main reason for his going was to sing, but as George notes, regretfully, pubs have changed.

‘They don’t listen to you now when you sing. There is nowhere now, nowhere at all.’

Latterly he has enjoyed the company of his grandchildren, and plays dominoes with them or sings. Keith is obviously one of his favourites.

‘Before ‘e started schoolin’, he used to come in here and ‘e could sing, really, when he were a little lad. I used to have him singin’ old songs. When we’d finished cows up in the morning. Given them their ‘ay. We used to sit on a truss ‘ay in corner like. I should be singing these old songs to ‘im, an’ ‘e learnt ’em off be ‘eart. ‘E could sing, like a little nightingale. [laughs] He always knew, I told him like, he’d remember it all his life. I bet ‘e does an’ all. ‘E’s not forgot it now.’

For George, singing is now entirely reserved for social occasions, such as an evening at the Community Centre or a family gathering. He does not admit to singing for his amusement. To be a ‘good’ singer in George’s estimation implies a willingness to contribute to the pleasure and enjoyment of others, a fulfilment of a social obligation. Of course, this does not preclude the importance of other qualities, such as self-confidence or a good voice, nor does it outweigh the need for a good song. However, it does represent an important slant of meaning, that it is an asset to be a singer if one is to be a valued member of the community. Today, such an assertion holds no truth but in the farming community of Fulwood and Ringinglow in which George grew up, it must have seemed a reasonable proposition.

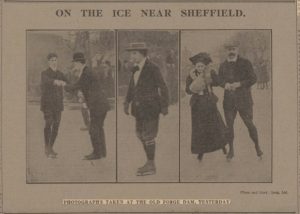

The skating was clearly organised and managed. At one point there is a gentleman in a dark suit and wearing a bowler hat. He is stationary in the middle of the ice and appears to be ensuring safety an suitabble behaviour. There are also men clearing away the loose ice created by the blades as the skaters twist and turn

The skating was clearly organised and managed. At one point there is a gentleman in a dark suit and wearing a bowler hat. He is stationary in the middle of the ice and appears to be ensuring safety an suitabble behaviour. There are also men clearing away the loose ice created by the blades as the skaters twist and turn