This is the last of four posts giving a brief history of Ringinglow

Brown Edge Quarries

Joseph Andrews of Green House Farm was listed as the quarry owner in White’s Directory of 1841. In 1845 Philip Andrews was a coal-owner and farmer in the area. The quarry had been operating since at least 1836 and produced good quality stone slates for roofing, flags and building. About 1860 it was owned by a Mr Chaddock then by Sam Hancock, an older relative of the Fulwood monumental mason. Later it was owned by his brother Henry some of whose actions have already been described. The quarry closed about 1873.

The Deep Sick Coal Pits.

About 250 yards west of Moorcot cottage and on the same side of the road as the Round House, was the first of two Deep Sick coal pits. Deep Sick was the name given to the start of the Fenny Brook which became the Limb stream. Shale and pudding holes were found approximately opposite the Ring o’ Firs farm and a shaft was later sunk a little further away, about 600 yards west of the Norfolk Arms. Both workings lie inside Lady Cannings Plantation. The coal was wound by a hand windlass and the tubs were pushed along the pit bottom over stone flags. It is thought that coal workings began at the time of the Dore Common Land allotment between 1809 and 1822.

Robert Trotter was married and living at Carr Houses in Fulwood when he started the Deep Sick coal pits, building a shed in which to sharpen tools near the first workings south of the Norfolk Arms. He traded his coal for lime from the lime workings at Stoney Middleton but he said that carters and others ‘pinched’ the coal so he came to live on the job and added a parlour to the cabin, so making ‘two stories lengthways’. He was helped in the business by his only son George. The land formed part of the Dore common enclosure allotments so he very reluctantly had to pay 5 shillings a year for his occupation of the house which, by then, was jokingly called Moorcock Hall. The payment did however entitle him to half yearly free dinners for all such tenants at the Rutland Rent audit held at the Peacock Hotel at Owler Bar, even though it disbarred any claim he might have had to squatters’ rights over the house. When Robert died his widow and son had the payment increased to three guineas a year. They could, though, rent out the mining rights.

The coal workings were abandoned by 1862 and the 1851 Dore census records George Trotter. aged about 67 being described as a coal-miner pauper, so it seems that mining was ceasing to be profitable for some time before the final closure. The Trotters remained in the house until Hiram’s widow moved out in 1887 and the house is reported as being abandoned between 1887 and 1892 according to one of her sons. It was demolished around 1911 with some of the stone used to build Mr Priest’s house, Moorcot, which was built on an adjoining plot.

The coal obtained from Ringinglow was of an inferior quality. Herbert Trotter reported that one load of the coal would produce ‘two loads of ashes and one of soot’. The local saying was that ‘you could boil owt and roast nowt’ with it. It also had a high sulphate of iron content which meant that sometimes it would explode with a crack sending burning pieces across the room. Herbert likened it to being at the 1854 battle of Balaclava.

There was another coal pit near Carsick Grange about 200 yards east of Carsick Hall.

The Wire Mill

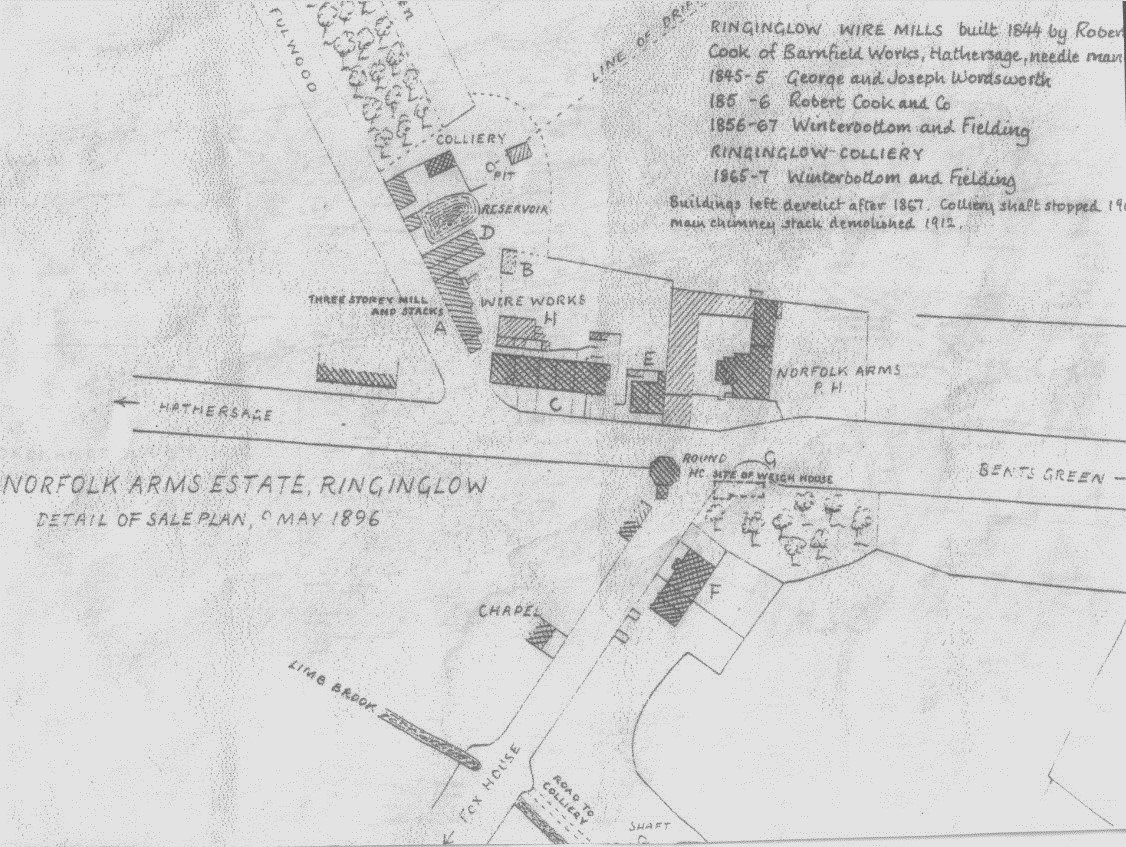

The Wire Mill was constructed on land immediately behind the row of terraced houses next to the Norfolk Arms with access from Fulwood Lane. A detailed layout is shown on the 1896 plan

The Mill was constructed in 1844 by Robert Cooke of Bamforth. George and Joseph Wordsworth operated there from 1845 until 1855 and Robert Cooke’s manager George Winterbottom of Batley took over the works and entered into partnership with a man called Fieldsend. They were advertising for workmen in 1862 in the following terms

“Wanted. Several cast steel wire drawers to draw from Nos 1 – 12 Needle Wire”.

Less than two weeks later there was a fire at the works. Rumour has it that it was caused by disgruntled workers from the Mill who believed it to be uninsured. That may in part explain the letter written to the editor of the Sheffield Daily Telegraph by the employers at the Mill.

The letter thanks all those who assisted in containing the fire. Mr W Swift for spotting it, Mr Charles Marsden, the Norfolk Arms landlord for organizing a party to contain the fire and stopping it spreading until the fire engines arrived. Engines came from the Sheffield Fire Office and succeeded in containing the blaze to the building in which the fire started without it spreading to the other mill. A considerable amount of valuable property was also saved from the debris through the perseverance of Mr Staniforth, the captain of the Sheffield Fire Brigade.

The last paragraph of the letter may well be sending a message to those responsible for the fire. It reads

“We also feel it is our duty to publicly state that the Sheffield Fire Office, with whom we are insured, have, through their secretary, Mr Esam, satisfactorily and promptly settled our claim and thus enabled us to proceed with our business without unnecessary delay”

It is signed Winterbottom and Fieldsend, Ringinglow, and dated 25th November 1862.

The plan also shows at its. Northernmost point, a colliery. An advertisement in 1860 invited investors to contribute towards an intended mine on the site which was to have a shaft of approximately 50 yards to be sunk.

Mining seems to have been carried on spasmodically. Winterbottom and Fieldsend used the coal mined to power the mill but their involvement ceased in 1867. A sale of the Wire Mill and the colliery complete with plant, steam engines boiler and boiler house, as well as other land, was advertised for sale in 1882. In 1901 the North end of the pit was deemed unsafe and blocked up, and the site was demolished along with the chimney which bore the date 1844, in 1912.

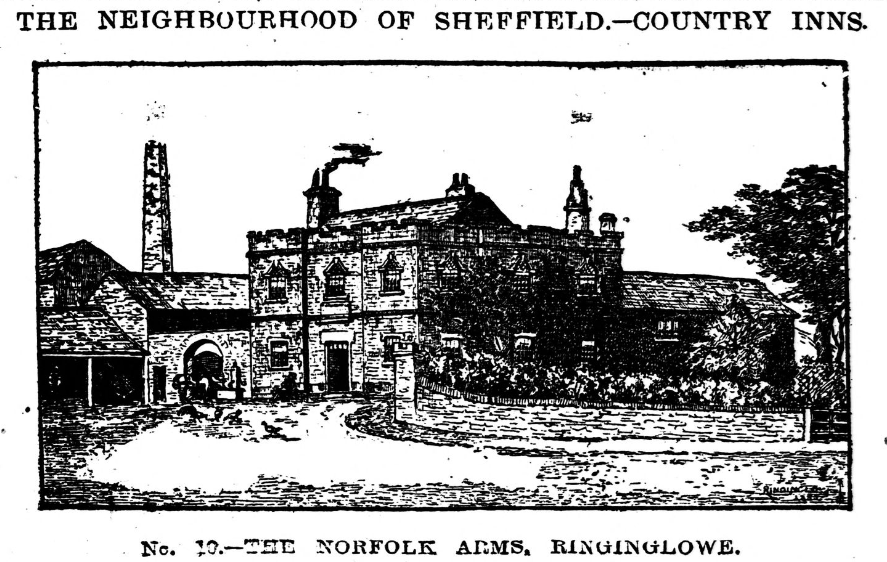

The chimney is shown behind the Norfolk Arms in the photograph that appeared in the Sheffield Independent of 13th February 1886. It is said that the lightning conductor on the chimney, after demolition, was made, by Hiriam Trotter, into toasting forks for everyone in Fulwood.